Sequential Overload in Pets

Stress isn't all bad. Stress is needed to avoid potential dangers; it's part of animals' natural responses to threats: if they don't respond to threats in nature, they don't survive!

Some level of good stress (eustress) is even needed for learning. Learn more in this blog on The Canine Learning Stress-O-Meter.

Certainly, too much stress can make learning less productive. But it doesn't, prevent learning. High levels of stress make certain kinds of learning much faster and longer lasting. For example, a stressed animal will be particularly efficient at learning cues that may signal a predator may be coming.

This is what Dr Maria Thaker and her colleagues found in their studies of eastern fence lizards [1]. These lizards see potential predators at a distance, then based on whether or not the predator tries to attack, the lizard learns to flea and hide. Lizards that were stressed even before the learning trials started fled sooner and hid longer from threats. Lizards with lower stress before the encounter did not learn to respond as quickly.

Stress primes the brain to learn to avoid potentially dangerous cues, while learning about good things is less efficient. Call it pessimistic mode: the faster learning is specific to perceived threats [2]. The negative associations learned while stressed also last a long time ... they're harder to get over.

That may be useful for the lizard: they're sought after prey - it's not paranoia when everyone is out to get them! But our dogs’ brains go into the same pessimistic mode when stressed - for some this might be in a visit to the vet. Now, what's good for the lizard, is not so good for our dogs.

Stress at the Vet

On my dog's first visit to a vet, everything was new: the lobby, check in, exam room, some guy in a lab coat ... and then the thermometer! He didn't like that last part. His mind likely connected each of those previously new things and the unpleasant process of getting his temperature taken. But this wasn't locked in as a fear like the stressed lizard. Not yet.

The next visit, however, he was a little unsure in the lobby, and a little unsure in the exam room. His stress level was slightly higher than the first visit. So, this time when he saw the lab coat and feels the thermometer his mind forms a much stronger association. This isn't just a second experience, but it's a second experience magnified by the sequence of mildly stressful events that led up to it.

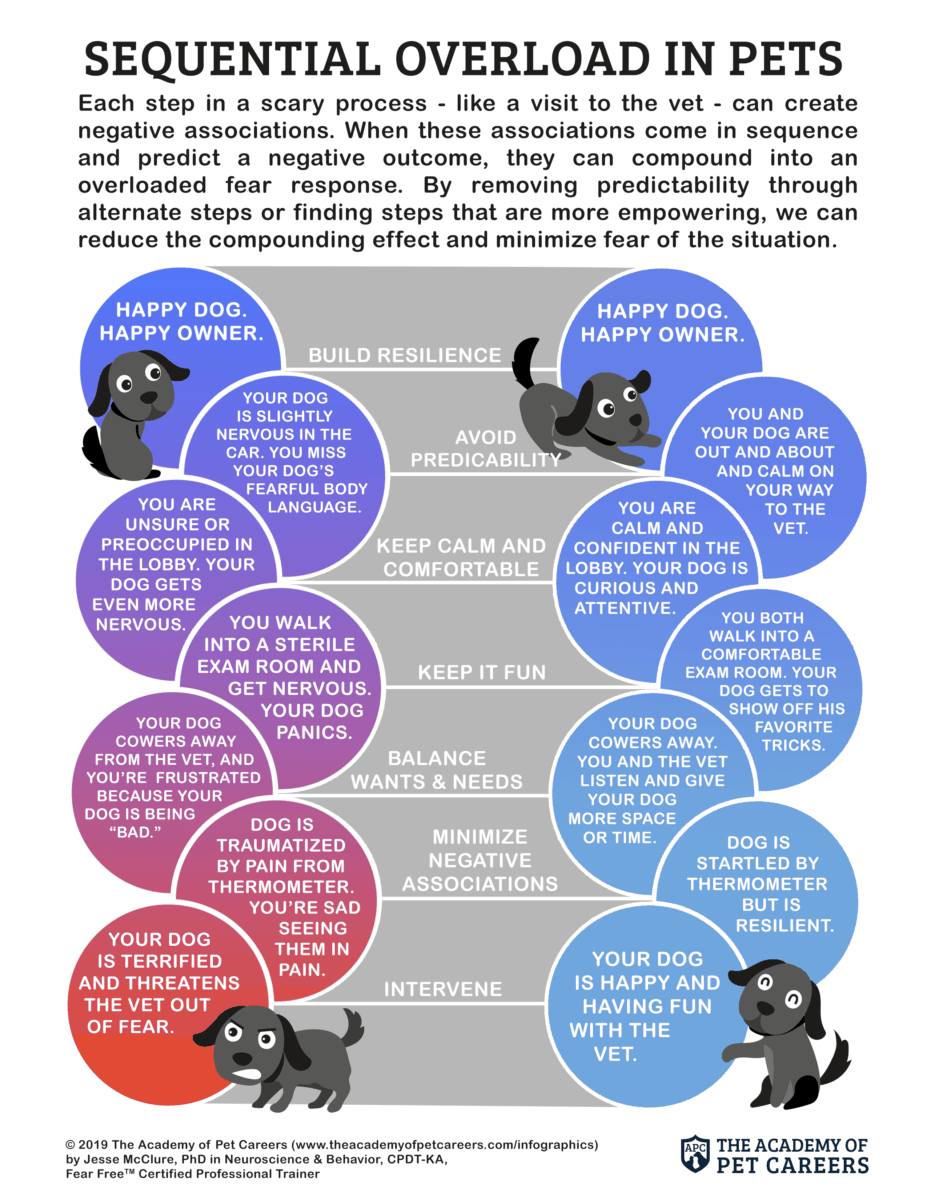

His learning that the lobby predicts the thermometer is magnified by the stress of the car ride. The learning that the exam room predicts the thermometer is magnified by the stress of the car ride and the lobby. The learning about the lab coat, in turn, is magnified by the stress of the car ride, the lobby, the exam room, and any other routine part of this sequence. The longer the sequence, the greater each bit of the sequence can be magnified by what came before it, resulting in a sequential overload. This can create fearful associations far out of proportion to what is actually happening.

Preventing Sequential Overload

So, what can we do? First, find a vet committed to minimizing fear, anxiety, and stress in the clinic (e.g., Fear Free certified vets); they can help with much of this. But the first steps are in your hands.

- Build a confident, resilient, empowered pet. Basic training, using force-free techniques, can build your dog's overall confidence. Dog sports and other healthy activities can help too.

- Avoid predictability. Start with the car ride: take car rides to places your dog enjoys more often than to places that may not be as much fun. Change up your route to the vet on occasion to help prevent certain roads or scenery from predicting what is to come.

- Remain calm and self-aware. Our dogs are keenly aware of our emotional states. If you are nervous or uncomfortable as you arrive at the vet, your dog will pick up on that which can add yet another accelerant to their stress. Center yourself, and if you are really having an off day, consider rescheduling or take time to do something for yourself before you bring your dog in.

- Have fun! Your vet may offer your dog some treats; ask if your dog can show off one of their favorite tricks to earn the treat. An earned treat contributes more to resilience than a free one. This can bring any stress levels back down breaking the cycle of increasing stress as the sequence continues.

- Advocate for your pet's emotional health. If you see that your dog is stressed, take them back outside for a minute and try again. If they remain too uncomfortable ask your vet which parts of the visit can be postponed. A little investment in time and effort now can prevent a lot of hassle and discomfort later.

These steps can help minimize negative associations with thermometers or needles or other things your dog may dislike. Your dog may never enjoy these parts of the vet visit, but we can help them not build up disproportionate fear responses.

While preventing problems is the best way to go, if your dog has already gotten off on the wrong foot with the vet or anywhere else, seek help from an experienced force-free trainer or behavior consultant to get back on track.

Footnotes

[1] Thaker, M., Vanak, A. T., Lima, S. L., & Hews, D. K. (2009). Stress and aversive learning in a wild vertebrate: the role of corticosterone in mediating escape from a novel stressor. The American Naturalist, 175(1), 50-60.

[2] Robinson, O. J., Overstreet, C., Charney, D. R., Vytal, K., & Grillon, C. (2013). Stress increases aversive prediction error signal in the ventral striatum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(10), 4129-4133.

Author - Dr. Jesse McClure

Dr. Jesse McClure has his PhD in Neuroscience and behavior and has been training dogs professionally for over 15 years. Dr. McClure has contributed to research in both animal communication and impulsive behavior. Currently he works with The Academy of Pet Careers doing behavior modification work for local dogs with severe behavior tenancies. Dr. McClure is also Fear Free™ Certified and has his CPDT-KA.